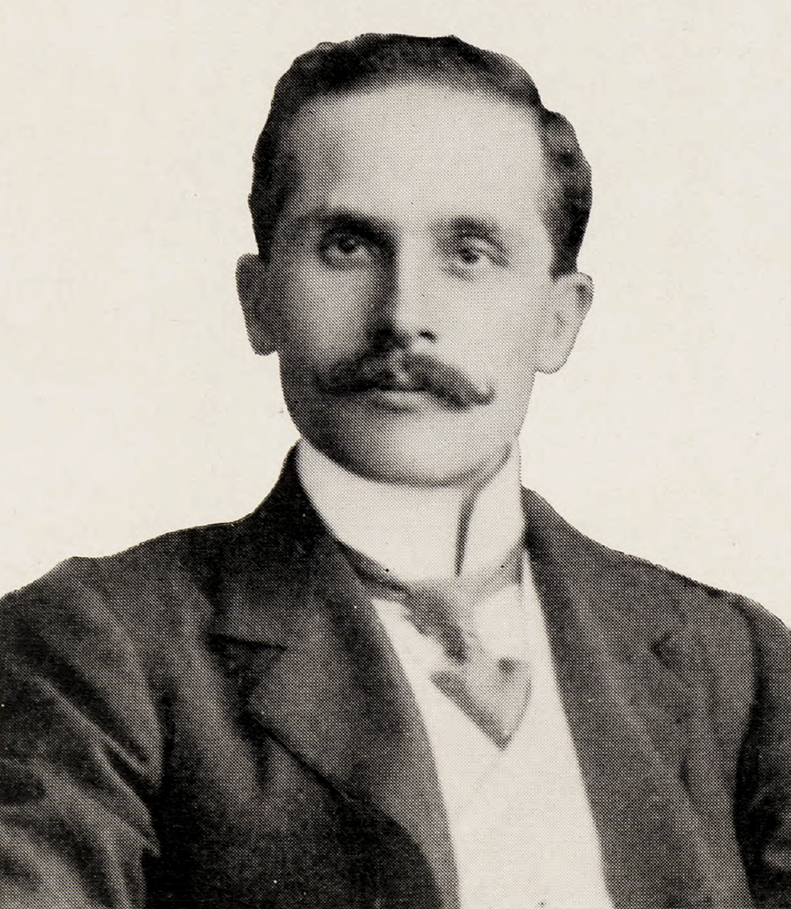

Domenico Borgia, 1906

UPDATED November 2021 with additional personal family information

Design-build architect and sculptor Domenico Borgia ran a highly successful family business providing a specific item—works in marble—to the construction trades in New York City circa 1900, perhaps working primarily with Italian speaking clients: priests buying altars for churches, undertakers needing head stones and mausoleums, general contractors needing showpiece marble fixtures, such as elaborate staircases.

Like mural painter Donatus Buongiorno (though exponentially more successful, financially), he was another educated, technically skilled Italian American business man who was trained in Italy before migrating and had a successful career in the U.S., though possibly invisible to the general populace, because he often worked in non-English-speaking U.S. communities, probably in his native Italian language.

Beginnings

Domenico Borgia was born in Barcellona-Pozzo di Gotto, Messina, Sicily, on September 8, 1869, into a family of marble workers with various industry skills, who migrated in stages to the U.S. in the late 1800s, seemingly enacting a plan to set up a vertically organized marble business—from quarry to finished product—with different family members running each section.

1888: Though Domenico was a middle child in the family, he appears to have been its director. The first to migrate, he arrived in New York in 1888, at age 19, with his father, Nicola Borgia, age 52 (born 1836). Possibly already trained as an architect in Italy, Domenico served apprenticeships for five years in American factories learning marble processing. During that time, the rest of the family migrated.

1890: Two of Domenico’s brothers came two years after him, in July of 1890, with intent to remain permanently (a question not asked in 1888, so we have no record of Domenico and Nicola’s claims): Alberto Borgia, age 28 (born 1862), mason, and Filippo (Philip) Borgia, age 10 (born 1880), no stated profession (too young). By the 1920s, this Alberto was traveling internationally as a salesman for the family.

1890: Domenico’s uncle, his father Nicola’s brother, also named Alberto Borgia, entered the U.S. two months after the two brothers in 1890. He was age 52 (born 1838), and declared intent to stay permanently. He boarded the boat in Messina, Sicily, not the more common Palermo, and travelled in Second Class, not the more common Steerage Class. His job “Comm,” presumed to be an abbreviation, in Italian, of a word derived from “commerciale,” is translated (written over in pencil on the manifest, presumably by a U.S. customs agent at Castle Garden) as “Broker,” suggesting this man was already a salesman for the family in Sicily, and he may have continued, from New York, to broker marble purchases from Sicily to the U.S. for their U.S. commissions.

Domenico’s two remaining living siblings (one other died as a child in Italy) followed.

1891: Vincentio (Vincenzo, Vincent), age 25 (born January 1869), arrived on June 8 or 11, 1891. Classified as a laborer on the manifest, he later described himself as a marble polisher.

1893: Tommaso (Thomas), born 1876, arrived 1893. He was a sculptor, later marble cutter, then building contractor/constructor.

There is no record of Domenico’s mother Teresa (Ficarra) Borgia ever living in the U.S., which suggests she died in Italy, most likely before 1888, when her husband and children started leaving Sicily.

New York Businesses

After completing his apprenticeships, Domenico quickly set up the family’s business. Borgia Marble Works was listed in five categories in an 1891 business directory (marble: altars, interior work, importers, modelers and sculptors, mosaics.) The business was incorporated in 1903, with Domenico as president, and his wife, Adele Borgia, and an Alberto Borgia, either his brother or uncle, as partner-officers, capitalized at $10,000.

The business’s 1906 address was Nos. 110–112 West End Avenue, New York City. By 1910, it was at 1133 Broadway, Room 1603, in an office building in a more central business location on Broadway near Union Square, with an additional partner-officer, Gaetano Parisi, now capitalized at $5,750.

Also in 1910, Domenico Borgia and Parisi established another company, Borgia Contracting Co., with a third partner-officer, Frederick V. Winters, also at 1133 Broadway but in Room 1605, capitalized at $10,000, and, with Domenico Cardo, Domenico Borgia also formed the Cardo-Borgia Stone Company to quarry and sell stone, capitalized at $10,000.

By 1910, Filippo Borgia was living in Queens, probably running the family’s cemetery monuments and mausoleums business, most likely to site the manufacturing business on less expensive real estate than Manhattan, and possibly also to be closer to the Roman Catholic Calvary Cemetery, where many products were delivered.

Ecclesiastical Projects

Borgia’s companies worked in New York City, other American cities, and Cuba. Their specialty was ecclesiastical works, encompassing altars for 100-plus Catholic churches in the United States, plus associated marble fixtures, such as communion rails and pulpits, many with sculptural elements and decorative mosaic pattern infills. They also made cemetery stones, monuments, and mausoleums.

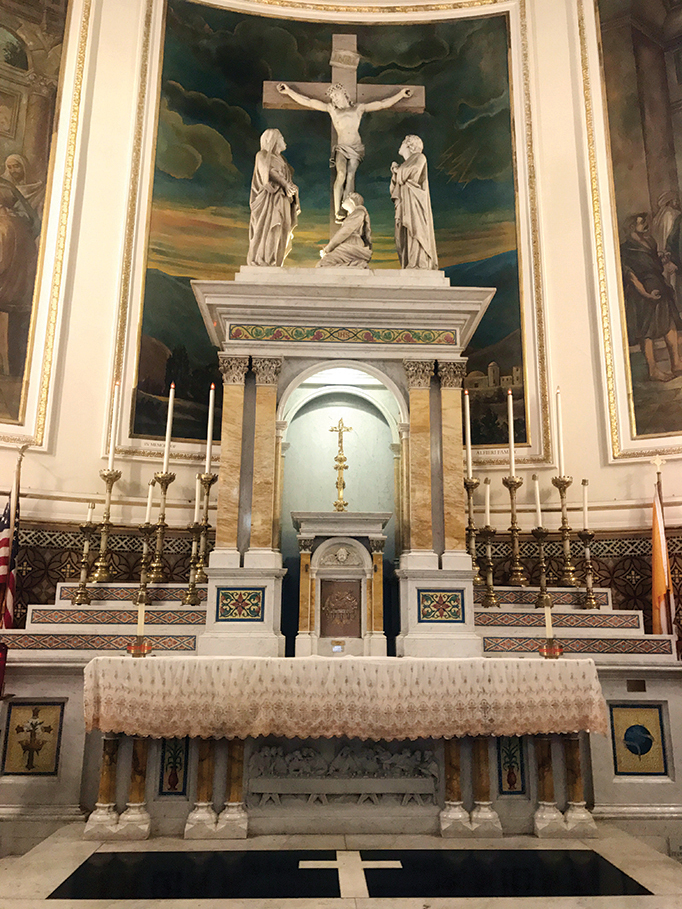

In 1903–1904, Borgia provided a collection of marble fixtures, all extant, for Most Precious Blood Church on Baxter Street in New York City for $5,750.00: a marble altar with multiple steps and columns, crowned with a freestanding Crucifixion sculpture on top, and with a bas relief Last Supper sculpture on the front face of its base, decorative mosaic patterns overall, and a supporting brick work foundation in the basement below. Also in the sanctuary are a communion rail and patterned floor of similar designs, most likely by Borgia, though not articulated in his contract with the church. Now removed, in the past there was a sculpted pulpit which was presumably provided by Borgia.

Altar, Shrine Church of the Most Precious Blood, New York, New York. Photograph ©2017 William Russo, all rights reserved.

Borgia Marble Works, Inc., Carrara marble altar with Crucifixion and Last Supper sculptures, 1903–1904, Shrine Church of the Most Precious Blood, New York, New York. Photograph ©2021 William Russo, all rights reserved.

Other Projects

In 1909, Borgia donated the base of Etiere Ximenes’ sculpture of Giovanni Verrazzano in Battery Park in Manhattan (extant.) A blatantly political public works project organized by Italian American businessmen, the sculpture was hustled together in a few months and opened on the same day as an event elsewhere in Manhattan for New York State’s 1909 Hudson-Fulton celebration, commemorating 300 years of Henry Hudson’s exploration of the river later named Hudson (and 100 years of Henry Fulton’s navigation of same in steam-powered boats.) The Italian immigrants wished to point out that the state had ignored the Italian Verrazzano, who “discovered” the Hudson River 85 years before Hudson, and to suggest that it was time to name something after him. (Fifty years later, their appeal was answered. A bridge was named Verrazzano, but with the surname misspelled; that was corrected in 2018.) https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/battery-park/monuments/1628

Ettore Ximenes, Giovanni da Verrazzano, 1909, Battery Park, New York, New York. Marble base by Borgia Marble Works, Inc., New York, New York. Wiki Commons photographer Zeete.

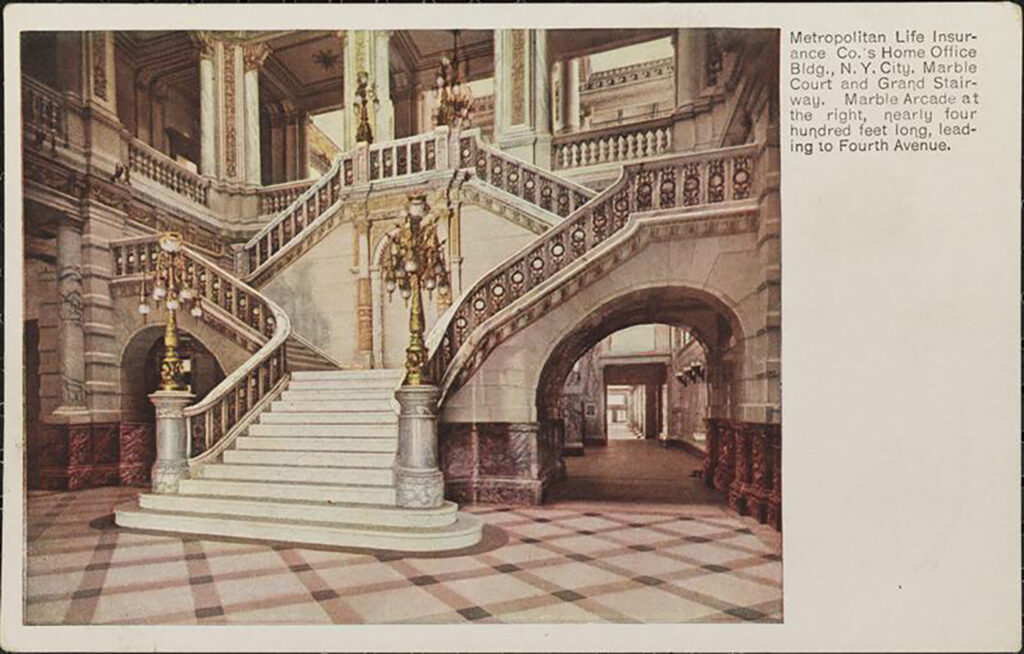

Also in 1909, Borgia directed the construction of an elaborate marble staircase on the ground floor of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Building on Union Square (building extant, but staircase demolished in a later modernization.) http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2011/06/1909-metropolitan-life-insurance-tower.html

Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower, Marble Court and Grand Stairway, ground floor entry interior, 1 Madison Avenue, New York, New York, period postcard, circa 1909.

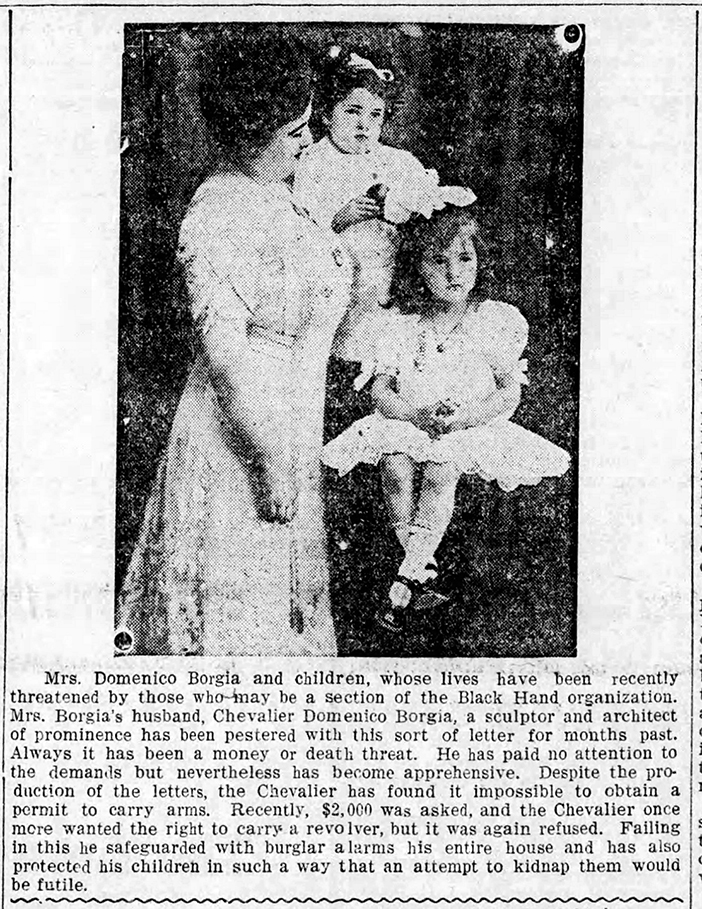

Black Hand

In 1910, Borgia was prominent enough to be threatened by the Black Hand (Italian thugs who preyed on other Italians in Little Italies in American cities), and he seemingly “fought back” by placing warning letters in newspapers. “Articles” about his wife and children (accompanied by photographs of them) are printed in at least two newspapers in the U.S., two days apart, in cities hundreds of miles apart, with the exact same wording, as if they were from a wire service. Is this how accomplished business people fought back against the Black Hand, by putting out a newspaper story saying “Don’t try anything, because I’m on to you, and I have notified the whole world?” A descendant reported recently that it was family lore that Borgia was substantially frightened—enough to buy a gun, and to move his family out of Manhattan for a period.

New Castle Herald, New Castle, Pennsylvania, August 19, 1910, page 6.

The Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, August 21, 1910, page 12.

Residences

In 1900, Domenico Borgia was the head of a family that included his two brothers (no father), renting a residence at 338 East 21st Street in New York City. From circa 1915 through the 1930s, he lived in single-family homes that he owned, with his wife Adele, whom he married in 1902, their three children—Domenico, Jr., Sabina, and Rosina—and servants, at 555, then 561, West 185th Street in New York City.

Most members of the family lived in upper Manhattan, often moving to new apartment buildings as neighborhoods were developed in the 1900s. Filippo moved to Queens by 1910, and by the 1920s, others had moved north to the Bronx and to West Chester County.

Naturalizations

All members of the family naturalized as American citizens, generally as soon as they were qualified to, 5 years after arrival.

Travel

Records of passports and manifest attest to substantial travel, for both business and pleasure, by multiple family members over the years, often with spouses. Domenico, who made many business trips to Cuba in the early years of the 1900s, delightfully, took his youngest daughter Rosina, then 20 years old, with him on a trip there in 1929.

Personal

Domenico Borgia died on February 6, 1937, at his office in New York City, of coronary sclerosis chronic myocarditis (heart attack), as reported by his daughter Sabina Carter. His funeral mass was held on February 9 at St. Elizabeth Church on 187th Street and Wadsworth Avenue, New York, a few blocks from his home of several decades. Founded in 1869, the parish moved one block to its current location in 1929, into a newly built building. Its massive, pre-Vatican II altar has hallmarks of a Borgia design: white marble, three towers, multiple levels, multiple sculptures of figures, multiple decorative features. Its two side aisle altars may also be by Borgia.

Domenico and his wife Adele are buried in Gate of Heaven Cemetery, Hawthorne, Westchester County, New York.

Domenico’s and his siblings’ descendants live all over the U.S. In the 133 years since the family’s arrival from Italy, several have been architects.

Leave a Reply