It was common that single men and married men who emigrated before their wives and children lived with another immigrant family before securing their own housing. The female head of the hosting household provided cooked meals and laundry service to her boarders in exchange for rent, so this was also a system of home-based work whereby women contributed to a family’s income, often substantially.

For many years in New York, Donatus Buongiorno and his wife Teresa Lagata hosted other Italian immigrant men, married and single, often relatives, as boarders in their home. Through the U.S. and New York State censuses, New York City directories, and my grandfather’s memoir, I have identified seven boarders they hosted from 1900 (and perhaps earlier) to 1919.

In 1907 they hosted four of my ancestors: my then-teenaged grandfather Domenico (Domenic) M. Troisi; his two, then-teenaged, brothers, Donato Paolo (D. Paul) Troisi and Dante Troisi; their then-57-year-old father (my great-grandfather), Beniamino (Benjamin) Troisi. Read their story here.

Three other boarders are described below.

Pasquale Sannino

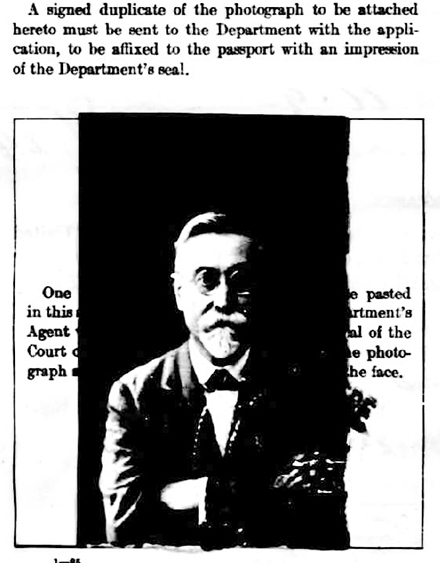

Pasquale Sannino, age 56, 1925 U.S. passport.

Buongiorno’s longest term boarder was Pasquale Sannino, who lived with the family for several decades, including in 1907 when my grandfather’s family of four joined the household for a year. In his memoir, my grandfather, Domenic M. Troisi, described Sannino as Buongiorno’s “life-long friend.”

Sannino was born in 1868 in Resina (now known as Ercolano), Compagnia, Italy, a small town on the slopes of Mt. Vesuvius outside Naples. Since Sannino was not from Buongiorno’s hometown of Solofra, Avellino, I suspect the two men met in Naples, after Buongiorno moved there in the 1880s. (Supporting this theory, the majority of Sanninos in Italy today are located in the Naples area, per telephone listings.)

Sannino emigrated to the U.S. in 1893, one year after Buongiorno. (With him on the boat is a man from Solofra: Francesco Cirino, age 29, laborer.)

Sannino became a naturalized American citizen in 1906, shortly before his first trip back to Italy, as was common. He also travelled to Italy in 1925. He died in New York in 1946.

From census reports and listings in city directories, I have confirmed that Sannino lived with the Buongiornos the entire time Donatus Buongiorno lived in New York, except for Buongiorno’s first few years (before his wife arrived in 1895), when Buongiorno shared apartments with other artists.

Donatus and Teresa Buongiorno and Pasquale Sannino (and other boarders) first lived together on East 12th Street in today’s “East Village” (then called the Lower East Side) in Manhattan and later in Italian neighborhoods in the Bronx.

Donatus and Teresa’s son Biagio Buongiorno joined the group, of course, when he was born in 1901.

After Donatus and his son Biagio Buongiorno returned to Italy in 1919, Sannino lived by himself in Manhattan.

Pasquale Sannino may also have also been a family member. In the 1900 U.S. Census (where he is misidentified as “Pascal”), Sannino is reported as Donatus Buongiorno’s cousin, but Italians use “cousin” loosely to identify any distant relative (and even very close friends who are not blood relatives), so I am not sure that information is reliable.

Also, I have been told by other researchers that census enumerators of this period weren’t precise, which I believe, as I’ve seen ample evidence. Besides “Pascal” cited above, there’s a Paolo on this sheet who is listed as “Powlo.” Apparently, sometimes the census enumerators stood in the stairwell of a tenement building, shouted up the stairs “Who lives here?,” and took information from anyone who replied.

Sannino was an “expert, artistic cabinet maker,” according to Domenic M. Troisi. In his vital records, Sannino is always identified as either a “wood worker” or “cabinet maker,” and seems to have work steadily in furniture factories in Manhattan.

My favorite record of Sannino’s connection to Buongiorno’s family is a memento he and Buongiorno made as a Christmas gift for my grandfather, Domenic M. Troisi, in 1916. It’s a cigarette box signed by both of them and inscribed to the then 22-year-old Domenic. I am certain Sannino made the box and Buongiorno painted its decorations, which include monograms of the makers’ names (DB and PS) and the recipient’s name (DMT), plus holiday greetings.

I also suspect Sannino made frames and stretchers for Buongiorno’s easel paintings, as some look hand- or custom-made.

Do you know more about Pasquale Sannino? I would love to hear from you. Please write to me, either privately at this e-mail address, or leave a comment below.

Felice Cuniberti

Also known as Felix M. Cuniberti

Another boarder in Donatus Buongiorno’s home in the 1900 U.S. Census is brother-in-law Felice Cuniberti.

I have not been able to determine Cuniberti’s familial connection to Buongiorno and suspect I can not assume the connection is through a sister. Perhaps the designation brother-in-law was assigned to more than the husband of a sister, as I know from birth records of Buongiorno’s siblings, which I have researched in genealogical archives, Cuniberti’s wife Clelia (see below) was not Buongiorno’s sister (though Buongiorno did have several sisters, and it’s possible Cuniberti was married to one of them before marrying Clelia.) If Italians called the husbands of siblings’ spouses and the husbands of one’s spouse’s siblings “brother-in-law,” then many more potential surnames are “in play,” making it difficult for me to trace the connection between Cuniberti and Buongiorno.

Born in 1870 in Naples, Cuniberti emigrated to New York in 1895 as an already-educated professional. Among the farmers, peasants and other, probably illiterate, craftsmen on his steerage-class manifest, his job of “forwarding agent” jumps out prominently (see line 6.) By 1900, he was working as a “customs house broker” per the 1900 U.S. Census.

He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1901, two days before he was issued a passport for his first return trip (of several) to Italy. In 1905 he applied for passports for his wife Clelia and two daughters, Teresa and Margherita, to emigrate to the U.S.

His continued professional employment in New York is evident from the titles and addresses in his documents: “forwarding agent” on his 1895 manifest, “Custom House Broker” in the 1900 census. He worked at a company called Morris European and American Express Company, which he left in January 1901 to form his own company, with partners, called Merchants European Express Co. In 1901 that company was located at 24 State Street; in 1905 it was at 59 Broadway. Both addresses are in lower Manhattan.

My favorite record of Cuniberti is a letter he wrote to The New York Times in reply to a letter from a local crank, Samuel Conkey. Conkey, having previously expressed his objections to pigeon shooting and deckle-edge pages in books, moved on to heavier matters in 1906, complaining about “undesirable foreigners,” including “Italian murderers and counterfeiters.”

Despite its somewhat broken English, Felice/Felix M. Cuniberti’s response to Conkey defending the honor of Italians is eloquent and restrained. It also gratifies me for another reason. It demonstrates that Donatus Buongiorno associated with intellectual thinkers who, like him, weren’t afraid to act on their principles and take public action in their new country against injustices and in support of their rights. See Buongiorno’s statement (perhaps ghost-written by Cuniberti, as I know Buongiorno’s English skills weren’t this good) in this 1908 Petition to U.S. Congress.

Do you know more about Felice Cuniberti? I would love to hear from you. Please write to me, either privately at this e-mail address, or leave a comment below.

Frank Caiazzo

Also listed as Donatus Buongiorno’s brother-in-law in the 1900 U.S. Census, I have not been able to learn anything else about Frank Caiazzo other than that he was a laborer who emigrated from Italy in 1900, as claimed in the census. There are no Caiazzos in the birth records of Buongiorno’s home town of Solofra, so he must have married into the family from elsewhere, most likely Naples or its environs. In Italy today, Caiazzos listed in telephone books live mostly around Naples, which supports this theory.

Do you know more about Frank Caiazzo or any of the men on this page? Perhaps you are a relative of them? If so, I would love to hear your family’s story and to see if we can fill in the gaps in my story. Please write to me! Either privately at this e-mail address, or leave a comment below.