Is it possible to attribute an unsigned painting? Yes.

How? With a preponderance of evidence.

Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, private collection

Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, in frame, private collection

Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, verso, private collection

My answer: Most likely yes.

Here’s a peek at our correspondence (which I am showing with the owner’s permission.) Her enthusiasm is so infectious; it’s the perfect example of the excitement I feel—and fun I have—when someone contacts me about a painting they own. Some of you have bought paintings and may recognize this feeling.

Owner of painting: This wonderful oil painting has had me looking for the artist for 38 years! Please tell me that I found the artist Donatus Buongiorno! I even took it to the Antiques Roadshow when they were here in Florida. It was given to me by a dear friend who passed away 10 years ago at the age of 87. I love your story, and I am so relieved to have finally found the artist! I hope!

———————————-

Me: I’m so glad you wrote to me! How did you find me online without knowing the artist’s name?

How did your friend acquire it, do you know? Did he or she know anything about where it came from or who owned it? I bought mine from a dealer who knew nothing, which is common.

What did the Roadshow tell you about it, and…most important…did you get on camera?!

———————————-

Screen grab of Schrevogel painting on Antiques Roadshow, PBS, used without permission. PBS: please contact me if we can set something up–or tell me to take this down, I will oblige.

Owner of painting: This painting is oil on wood. It was given to me from a friend who didn’t tell me the story behind it, as she had Alzheimer’s. That’s why it took me so long to identify!! I was watching Antiques Roadshow on TV when I saw a painting of a Western artist, Charles Schrey (something)1 and Googled it and it took me to you!! I almost jumped out of my skin!!! I saved the original nails to preserve this antique.

———————————-

Me: And I jumped out of my skin when I saw your photos and read your fabulous story.

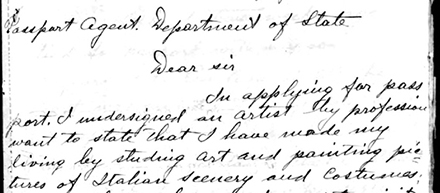

I am pretty certain this painting is by Donatus Buongiorno for the following reasons: there are other versions of it which are signed; the method of paint application (especially in the background) is consistent with other (signed) paintings; I have another painting (of a completely different subject) on the same kind of board (instead of canvas), including its beveled edges; I have other paintings in the same kind of frame; in a 1919 passport application (see photo) for one of his many trips to Italy, Buongiorno stated that he “made his living by…painting…Italian…costumes,” perhaps documenting the disappearing 19th-century clothing of rustic people from Naples and his rural hometown, and this man’s image may be from that effort.

Excerpt of 1919 passport application of Donato Buongiorno, U.S. Dept. of State, used with permission

It also may be a good copy by someone else, maybe even a student under his direction. My non-paint evidence (style of frame, style of board that it’s painted on) doesn’t preclude Buongiorno’s involvement with those items on someone else’s behalf.

A mystery I can’t explain: Why my Donatus Buongiorno website (donatusbuongiorno.com) popped up in your search on Charles Schreyvogel, a painter of western U.S. horse scenes that look nothing like Donatus Buongiorno’s paintings of Neapolitan Italians. I don’t have unrelated keywords hidden in the site, I swear, and all I can see that the two painters’ works have in common are their 19th-century, academic (realistic) “looks” and funky, elaborate 19th-century gilded “compo”2 frames—which these two artists also have in common with a couple thousand other 19th century painters. Thank heavens for the internet reading our minds and putting us together!

———————————-

Examples

Man Lighting Pipe, signed, collection of author

Man Lighting Pipe, signed, private collection, used with permission

Man Lighting Pipe, signed, private collection, used with permission

Man Lighting Pipe, signed, collection of California dealer, used with permission

There are four other versions of this painting extant (that I know of)—this model, in exactly the same pose with exactly the same clothing (though different colors)—which are all signed. I own the first painting shown, and the other three are here with permission from their owners. (The last one, by the way, is currently for sale on eBay from a very nice dealer in California.)

Could my inquirer’s painting be a fifth?

2. Outlines

Man Lighting Pipe, signed, detail of edge of hat showing blue outline of under-drawing, collection of author

Man Lighting Pipe, signed, detail of edge of shoulder showing blue outline of under-drawing, collection of author

My painting has blue lines around some shapes (see two detail photos) which my conservator thinks were from a pattern Buongiorno traced onto the canvas, suggesting he had a master drawing from which he made multiple paintings.

3. Painting Style

Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, private collection

Painting with similar background to Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, collection of author

Painting with similar background to Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, collection of author

The paint application in my inquirer’s painting, especially in its background, is consistent with other, signed, paintings. See photos.

4. Materials

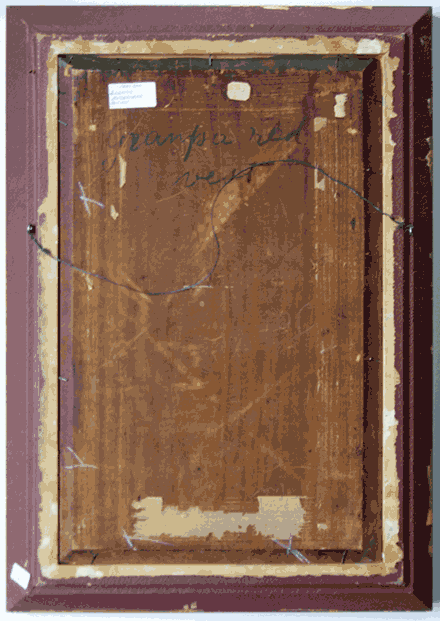

Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, verso, private collection

Verso of painting on same type of beveled, wooden board as Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, collection of author

I own another painting (of a different subject) which is painted on the same kind of board that my inquirer’s painting is on (though of larger dimensions), including beveled edges on the verso side, so Buongiorno may have had a source for these boards at one time.

5. Frame

Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, in frame, private collection

Painting in elaborate composition frame similar to Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, collection of author

Painting in elaborate composition frame similar to Man Lighting Pipe, unsigned, collection of author

The style of frame that my inquirer’s painting is in is consistent with other, signed, Buongiorno paintings. See photos of two I own. When I acquire a painting in a period frame (circa 1900), I assume it’s original, perhaps chosen by Buongiorno himself.

Why didn’t Donatus Buongiorno sign this painting?

He seems to have been a master self-promoter, even changing his name from Donato (Italian) to the more flamboyant Donatus (Latin)3, which he used in his art career, and presumably he had a sufficient ego to claim his product.

The lack of signature alone isn’t enough to definitively say he didn’t paint it, as there were two categories of painting that I know of which he did not sign: 1. His church mural commissions (because it was not the custom, family members were told), and 2. Duplicates. Yes! I have definitive family proof that he acknowledged making duplicates.

After their parents died, my grandfather and his brother (who were Buongiorno’s nephews) commissioned Buongiorno to paint each of them a set of portraits of their parents (from photographs.) The first set is signed, and the second set is not—being copies of the first. Buongiorno told them this was the conventional way to identify the “originals” as being different from the “copies.” (I assume this was a “rule” of the academic painting system, but I have never seen it documented. If anyone knows, please inform me.) This story was handed down to the family members who inherited the four paintings.

Who else might have painted this painting?

Buongiorno also taught, which may have included taking private students into his studio to apprentice one-to-one. It was common to have the student learn by copying paintings, including the master’s. It’s possible this “fifth” painting is a copy of one of Buongiorno’s four versions of it, and, for whatever reason, the student didn’t sign it.

What do you think? Is this painting by Donatus Buongiorno?

Postscript: The owner would part with this painting at a very reasonable price to a member of our family. If you are interested, contact me.

FOOTNOTES

1. Charles Schreyvogel.

2. Compo is short for “composition,” the plaster and glue material used to make the decorative floral sculptures on the fronts of those frames.

3. This was a trend among some late 19th century artists, apparently. I’ve never found an explanation for it. The most prominent example I know of is French painter Carolus-Duran, who was born Charles Auguste Émile Durand.